How can I not offer you my thoughts on the most famous poem ever to feature an albatross? It may surprise you to know that Samuel Taylor Coleridge had never seen one of us before writing The Rime of The Ancient Mariner. The archaic language Coleridge uses in The Rime gives the poem a powerful sense of timelessness and helps to make it clear the real voyage undertaken by the mariner is an interior voyage into the deepest realms of the collective unconscious. The collective unconscious is the home of the archetypes that govern all life on Earth; it is the instinctual life of the psyche that you humans share with all other creatures, though you so often want to believe otherwise.

The unconscious speaks to us in symbolic images, not in words. These images can be baffling and terrifying in many different ways; often they convey stark emotional truths to you humans about parts of your psyche that you would prefer not to confront. Your overwhelming human instinct is to flee from these images … You perceive them to be close harbingers of psychosis and madness. The wedding guest upon whom the ancient mariner descends at the beginning of The Rime, though initially irritated by the old man’s obdurate presence, quickly becomes fearfully mesmerized by the mariner, as if clearly sensing the power of his story:

He holds him with his skinny hand, 'There was a ship,' quoth he. 'Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!' Eftsoons his hand dropt he. He holds him with his glittering eye— The Wedding-Guest stood still, And listens like a three years' child: The Mariner hath his will. The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone: He cannot choose but hear; And thus spake on that ancient man, The bright-eyed Mariner

It is the genius of this poem to create a situation in which the human character cannot flee from the frightening images that assail him. As the mariner says at the end of The Rime:

O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been Alone on a wide wide sea: So lonely 'twas, that God himself Scarce seemèd there to be.

The mariner’s voyage begins in ordinary enough fashion as his ship is carried into the southernmost Atlantic, but then it becomes locked in ice. There seems no hope of escape until the giant albatross appears, bringing with it a wind that frees the ship:

The ice was here, the ice was there, The ice was all around: It cracked and growled, and roared and howled, Like noises in a swound! At length did cross an Albatross, Thorough the fog it came; As if it had been a Christian soul, We hailed it in God's name.

The albatross playfully follows the ship, partakes of the food the sailors offer, and observes their religious rituals. The human crew freely allows themselves to believe in the albatrosses magical powers to create the wind.

It ate the food it ne'er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariner's hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon-shine.’

Both bird and human participate naturally and fully in each other’s mystique, until the mariner inexplicably kills the albatross. The wedding guest’s unease increases as the old man approaches this strange turning point in his story:

'God save thee, ancient Mariner! From the fiends, that plague thee thus!— Why look'st thou so?'

The mariner responds: “With my cross-bow I shot the ALBATROSS.” His slaying of the albatross is not presented as an act of rational consciousness. It is an impulse of unconscious caprice … Or of inescapable unconscious fate. The mariner’s crime against nature has immediate consequences for the mariner’s ship, which is blown around the Horn and north into the Pacific by “the spirit nine fathoms deep,” finally becoming trapped in the hot doldrums of the equator.

The Sun now rose upon the right: Out of the sea came he, Still hid in mist, and on the left Went down into the sea. And the good south wind still blew behind, But no sweet bird did follow, Nor any day for food or play Came to the mariner's hollo! And I had done a hellish thing, And it would work 'em woe: For all averred, I had killed the bird That made the breeze to blow. Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay, That made the breeze to blow! All in a hot and copper sky, The bloody Sun, at noon, Right up above the mast did stand, No bigger than the Moon. Day after day, day after day, We stuck, nor breath nor motion; As idle as a painted ship Upon a painted ocean. Water, water, every where, And all the boards did shrink; Water, water, every where, Nor any drop to drink. The very deep did rot: O Christ! That ever this should be! Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs Upon the slimy sea. About, about, in reel and rout The death-fires danced at night; The water, like a witch's oils, Burnt green, and blue and white. And some in dreams assurèd were Of the Spirit that plagued us so; Nine fathom deep he had followed us From the land of mist and snow. And every tongue, through utter drought, Was withered at the root; We could not speak, no more than if We had been choked with soot.

Dying of thirst and exposure, the younger sailors finally turn on the old mariner:

Ah! well a-day! what evil looks Had I from old and young! Instead of the cross, the Albatross About my neck was hung.

This is a key climactic image in the mariner’s story. The Christian conventions that have previously governed his spiritual life are thrown aside and replaced by a new, deeper myth—an unconscious symbol of Nature in the form of the giant albatross.

Amidst his psychic and corporeal suffering, the mariner sees a mast and sail approaching, and thinks at first that rescue is close at hand.

At first it seemed a little speck, And then it seemed a mist; It moved and moved, and took at last A certain shape, I wist. A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist! And still it neared and neared: As if it dodged a water-sprite, It plunged and tacked and veered. With throats unslaked, with black lips baked, We could nor laugh nor wail; Through utter drought all dumb we stood! I bit my arm, I sucked the blood, And cried, A sail! a sail! With throats unslaked, with black lips baked, Agape they heard me call: Gramercy! they for joy did grin, And all at once their breath drew in. As they were drinking all.

It soon becomes apparent, however, that this ship bears a strange aspect. It appears to carry a crew of only two—Death and the woman “Life in Death,” who are playing a game of dice for the lives of the mariner and his shipmates.

The western wave was all a-flame. The day was well nigh done! Almost upon the western wave Rested the broad bright Sun; When that strange shape drove suddenly Betwixt us and the Sun. And straight the Sun was flecked with bars, (Heaven's Mother send us grace!) As if through a dungeon-grate he peered With broad and burning face. Alas! (thought I, and my heart beat loud) How fast she nears and nears! Are those her sails that glance in the Sun, Like restless gossameres? Are those her ribs through which the Sun Did peer, as through a grate? And is that Woman all her crew? Is that a DEATH? and are there two? Is DEATH that woman's mate? Her lips were red, her looks were free, Her locks were yellow as gold: Her skin was as white as leprosy, The Night-mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she, Who thicks man's blood with cold. The naked hulk alongside came, And the twain were casting dice; 'The game is done! I've won! I've won!' Quoth she, and whistles thrice. The Sun's rim dips; the stars rush out; At one stride comes the dark; With far-heard whisper, o'er the sea, Off shot the spectre-bark. We listened and looked sideways up! Fear at my heart, as at a cup, My life-blood seemed to sip! The stars were dim, and thick the night, The steersman's face by his lamp gleamed white; From the sails the dew did drip— Till clomb above the eastern bar The hornèd Moon, with one bright star Within the nether tip. One after one, by the star-dogged Moon, Too quick for groan or sigh, Each turned his face with a ghastly pang, And cursed me with his eye. Four times fifty living men, (And I heard nor sigh nor groan) With heavy thump, a lifeless lump, They dropped down one by one. The souls did from their bodies fly,— They fled to bliss or woe! And every soul, it passed me by, Like the whizz of my cross-bow!

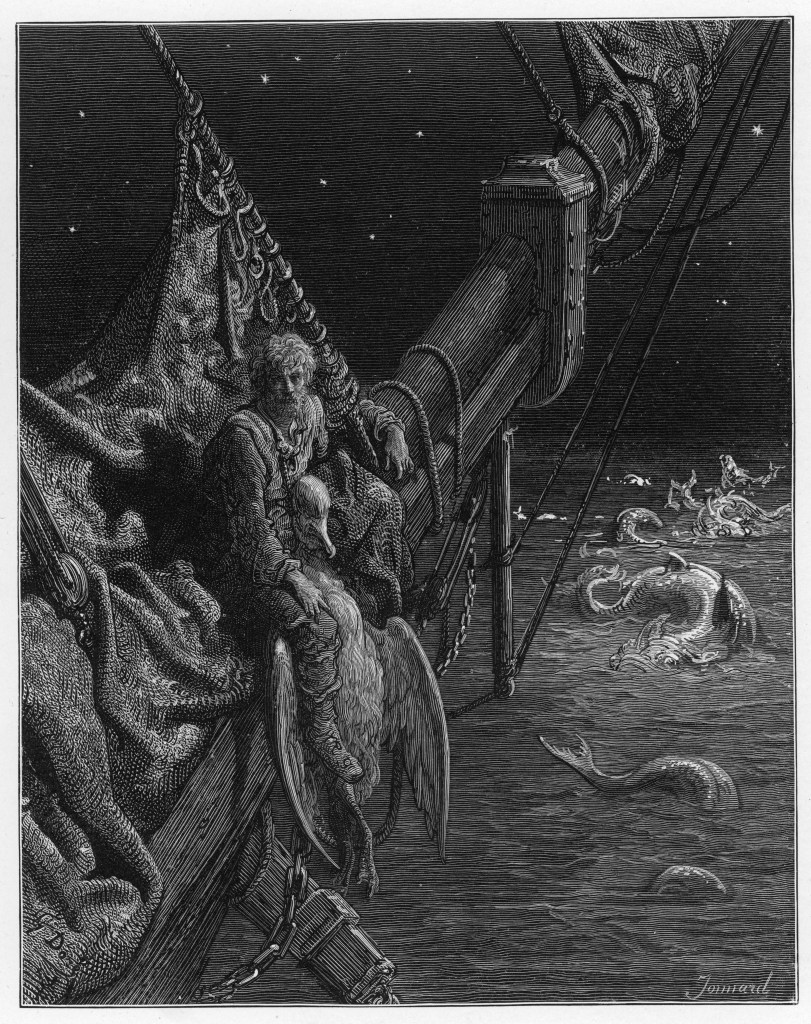

The mariner, his life claimed by the lady “Life in Death,” is now utterly alone, deprived even of the sustenance of his Christian god. Unable to pray, he can only watch the mesmerizing movement of sea snakes near the ship.

The many men, so beautiful! And they all dead did lie: And a thousand thousand slimy things Lived on; and so did I. I looked upon the rotting sea, And drew my eyes away; I looked upon the rotting deck, And there the dead men lay. I looked to heaven, and tried to pray; But or ever a prayer had gusht, A wicked whisper came, and made My heart as dry as dust. Beyond the shadow of the ship, I watched the water-snakes: They moved in tracks of shining white, And when they reared, the elfish light Fell off in hoary flakes. Within the shadow of the ship I watched their rich attire: Blue, glossy green, and velvet black, They coiled and swam; and every track Was a flash of golden fire. O happy living things! no tongue Their beauty might declare: A spring of love gushed from my heart, And I blessed them unaware: Sure my kind saint took pity on me, And I blessed them unaware. The self-same moment I could pray; And from my neck so free The Albatross fell off, and sank Like lead into the sea.

The blessing of the sea snakes seems at first to be no more rational an act than the slaying of the albatross, but the symbol of these creatures at this point in the mariner’s story is perfectly apt. No creature is farther from your human experience of life than the snake. When you humans see a snake you are terrified because you think you are seeing something deadly and utterly alien. But what you are really seeing is something very familiar, something latent and undiscovered within yourselves, something you think you have mastered and transcended but which lies coiled and ready to strike out of the unconscious at any moment, much as the ancient mariner’s irrational impulse struck at the albatross. In the body of a snake you humans see the pure primal energy from which you emerged and to which you will return; you see the destructive as well as the creative components of that energy, and this frightens you.

Here in this part of The Rime the mariner is finally forced to confront this part of his psyche. Watching the snakes dancing in the water, he comes to see their beauty. I think the mariner is able to see the unity of all earthly life and his undeniable membership in that unity. Only by loving the snakes, in all their aspects, can he try to use their energies constructively. The blessing of the water snakes is an instinctual, symbolic response; it is the turning point in the mariner’s psychological transformation. In this moment the albatross, having performed its sacrificial duty, slides off the mariner’s neck and into the sea, returning to the collective unconscious. And the familiar comfort of his Christian god is returned to the mariner.