It’s hard for me to believe that 35 years have passed since the Chernobyl disaster. I was a callow graduate student listening to the news when there was a mysterious story of radiation alarms going off in Sweden. Diplomatic inquiries were made. Very slowly, the grim details and images began emerging. Soviet state television and radio finally announced there had been “an accident” and immediately began broadcasting classical music, a practice previously reserved for the deaths of Soviet premiers.

Sixty people died in the reactor explosion and the immediate, frantic effort to put out the apocalyptic fire, and likely thousands more died from the effects of radiation exposure. A 400 hectare tract of pine trees near the reactor site were killed outright by the initial radiation and then bulldozed and buried in the cleanup. The Soviets tried using a fleet of robots to clean up debris from the explosion, but the radiation was so intense that the robots’ electronics were fried and soldiers had to be used to bury radioactive debris. Many debris burial sites exist in the area. 100,000 people were permanently evacuated from a 1,000 square mile exclusion zone around the Chernobyl plant. The gray, architecturally dystopian Soviet city of Pripyat, founded in 1970 as an “atomgrad” to house the Chernobyl work force, is now a post-nuclear ghost town, its street roamed only by sad, homeless dogs.

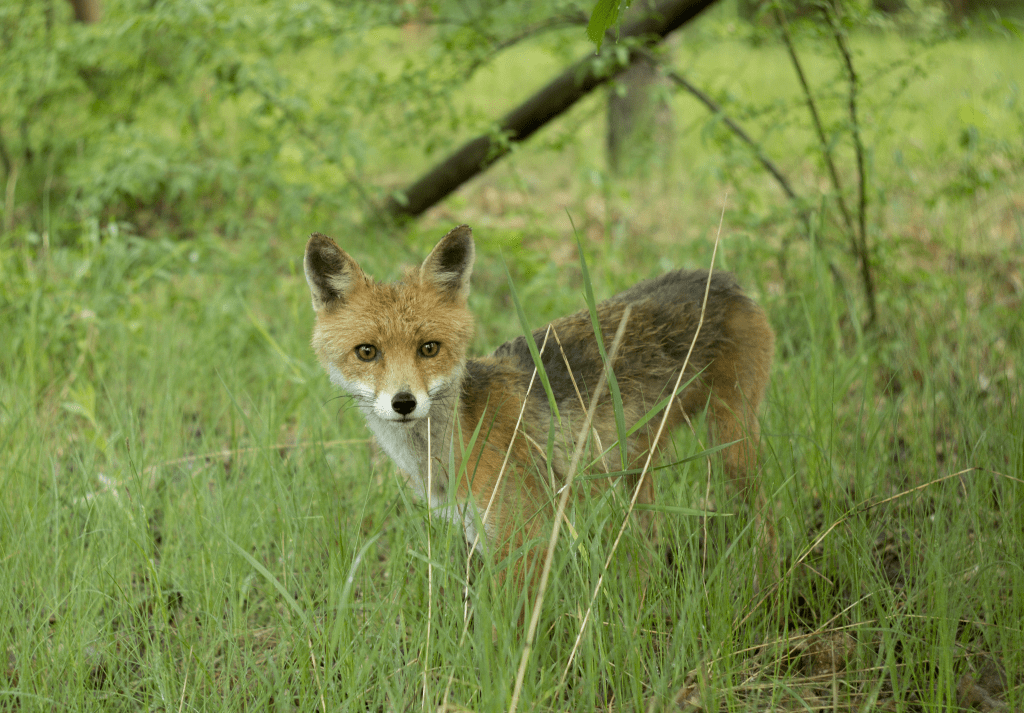

The explosion and fire at Chernobyl released 100 times more radiation then the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. While most of the radiation decayed within a year of the accident, many long-lived heavy isotopes remain, like strontium-90 (28 year half life), cesium-137 (30. year half life), americium 241 (432 yr. half life), and three isotopes of plutonium with half lives from 88 to 24,000 years. It is fairly well known now that, despite the radiation exposure, the ~1,000 square mile Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) has become a marvelous story of ecological resurrection. If the wild creatures in the CEZ had life spans as long as humans, the radioactive contamination they carry would certainly be much more problematic, but the wildlife populations in the exclusion zone are thriving, so much so that the CEZ is now the third largest nature reserve in Europe and the United Nations Environment Programme is working with the governments of Ukraine and Belarus to make the area a permanent biosphere reserve.

As is the case with carbon dioxide, trees are vital agents for sequestering radioactive elements. When a wildfire (likely caused by arson) tore through 11,000 hectares in the exclusion zone, radioactivity was re-released into the atmosphere. Now new growth can be seen in the understory:

Nuclear reactors require access to large volumes of cooling water, which the Pripyat river provided. Now the river and its tributaries support large populations of fish. A 2018 study in Environmental Science and Technology (Lerebours et al.) examined the effects of radiation exposure on perch and roach collected from lakes in the exclusion zone. While the study did find elevated incidence of reproductive abnormalities in the fish, no significant effects were seen at the population level: these fish have high fecundity and the populations as a whole are healthy and thriving, though you wouldn’t want to eat these fish. The same appears to be true for the Wels catfish and smaller ide that inhabit the erstwhile reactor cooling water ponds:

The birds of Chernobyl are perhaps the most amazing survival story of all. In a study published in Nature in 2014, Galvan et al. collected feather and blood samples from 16 species of birds found in the exclusion zone, measuring body weight and analyzing levels of DNA damage and endogenous anti-oxidants, molecules that would protect a bird against the ionizing, free-radical forming, effects of radiation. Incredibly, for 14 of the sixteen species studied, birds living in the zones of highest radiation had better overall body condition, higher levels of anti-oxidants, and decreased levels of DNA damage than birds living in areas with less radioactive contamination.

The two species in the study that did not fare well after the Chernobyl accident—barn swallows and great tits—use very high levels of their innate anti-oxidants to produce pigments in their feathers, and may simply not have enough left over to protect themselves against elevated levels of radiation. If you’ve ever seen a barn swallow up close, you know how intensely luminous their iridescent feathers are. Now we know in a new way the high metabolic cost for producing such beauty.

Clockwise from top: Hawfinch, Eurasian Eagle Owl, European Honey Buzzard, Black Grouse, Barn Swallow.

Gary wolves are another stunning success story in the CEZ. Freed from human hunting and persecution, wolf populations inside the exclusion zone are seven times higher than outside. Together with brown bears, wolves are the apex predators in the CEZ, keeping populations of roe deer and bison in check.

Rare, wild Przewalski’s horses, one of Earth’s more endangered animals, roam freely in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

In his surreal 1979 film Stalker, Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky tells the story of one man with a gift (the Stalker) who leads seekers into a mysterious place called the Zone where a person’s one greatest wish can be granted. But the Zone is a dangerous place, because one’s conscious wise usually doesn’t align with what the unconscious is thinking in any given moment. Stories emerge of previous seekers who find only unhappiness and even death after leaving the Zone. At the end of the film, none of the people led into the Zone by the Stalker dare to cross the final threshold into the sanctum where their wishes will be granted. Conscious, rational caution and a healthy respect for the unconscious trickster in the human psyche prevail.

In the years preceding the Chernobyl disaster too many people ignored too many safety warnings from the world of conscious, rational science and fooled themselves into a complacency that believed it could casually control the cosmic forces that created us. In the second hour of April 26, 1986 the threshold was finally crossed and the cosmic forces exacted the terrible price for human hubris. I think we all wish that the people who died at Chernobyl have been magically transported to existences with happier circumstance, but the resilient resurrection of so much wildlife in the exclusion zone seems nearly as miraculous.

There should be a hefty dose of bittersweet irony for all of us, however, to know that in this land we have so contaminated for our own survival, the wild creatures of Chernobyl are thriving precisely because we humans are not present. We are by far the most destructive agents for wildlife survival. The Earth has been sending us new and powerful warnings about our destruction of Nature … Are we listening any better than we did 35 years ago?